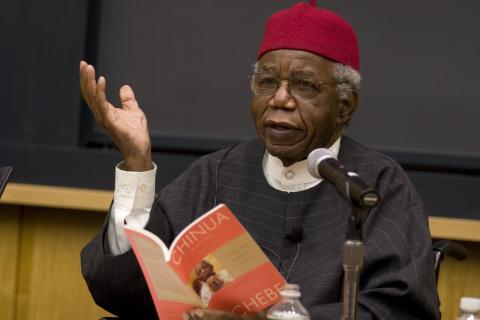

The Place of Chinua Achebe in History By George C E Enyoazu

Introduction:

During the colonial era: 1870-1960, Africa as a whole did not prove particularly attractive to the European investors. 9.3 percent of French overseas investment went to Africa, while 21% of British capital went there. South Africa got 15 percent of the total funds invested in British Africa (Duignan, and Gann, ed. 1975 p.26). South Africa got that major chunk for obvious reasons; meaning that the rest of British Africa was left with only 6 percent of British investment capital. Why would this be, irrespective of the scramble for Africa? And this scramble led to its partitioning amongst the European colonial powers, of which Britain and France were the main beneficiaries. The concise answer is that with the end of slavery, Europe wanted to legitimise its trading in Africa, in order to exploit the continent. According to African history:

Explorers located vast reserves of raw materials,

They plotted the course of trade routes,

Navigated rivers, and identified population centers which could be a market for manufactured goods from Europe.

They dedicated the region's plantations and cash crops workforce to producing rubber, coffee, sugar, palm oil, timber, etc for Europe.

And all the more enticing, they set up colonies which gave the European nation a monopoly.

In other words, the European economic interest precluded real investment in Africa. They wanted Africa as a cheap source of raw materials for their industries, and a large market for their finished products. From slavery to colonialism, Africa was looked upon as a source of manpower and raw materials which aimed at creating wealth for the West. Let’s just ponder on this for a moment!

Moreover, Africa has been stereotyped by the same people who plunder her. They had given their jaundiced image of the continent and her people to the world through literary and historical narratives, and distorted worldview. These became the impressions the world had of Africa. As John Edwin Mason puts it, the stereotypes included:

an unspoiled paradise of people and wild animals, living in harmony with nature

a primitive backwater trapped in a timeless, tribal past

a place where dangerous diseases and even more dangerous men wreak havoc

an exotic wonderland of bizarre and outlandish people

a broken place of collapse, death, and decay

These being the case, the Europeans felt they were on a holistic mission, and doing us favours by dismantling our primitivity and giving us illumination. Conversely, Africans needed to free themselves from the image they had been given. This image was classified by Morris Turner as: subjugated dehumanization, omission and subjection categorizations, which plagued Africans and the continent for hundreds of years. Turner stressed that a category that stands out is the perception of being “African”, and Being “Black”. He tones that “The notions of being African have to be seen through European lenses, and classified through a European projection.” Thus, freeing themselves from being seen through the prism of the European meant that Africans needed to let the world know who the real African was. But the setback was that there was no African who could challenge the prejudice and tell the African story. That was one of the moments the truth of one of Achebe’s wise sayings came alive: “If you don’t like someone’s story, write your own.”

Achebe as an Agent of Change:

Compelled by the need to tell the African story, Chinua Achebe stepped into the picture, and stood in the gap with his much acclaimed first novel “Things Fall Apart” in 1958.

In its posthumous tribute to Prof Achebe, the New York Times wrote, “Things Fall Apart” gave expression to Mr. Achebe’s first stirrings of anti-colonialism and a desire to use literature as a weapon against Western biases. As if to sharpen it with irony, he borrowed from the Western canon itself in using as its title a line from Yeats’ apocalyptic poem The Second Coming.”

In what seems like a contradiction, Achebe who was committed to undoing the negative impact of colonialism on the African culture and its people, felt that his best bet would be to use the platform provided by colonialism to do the fight. That platform was the language of the colonizer: English language. Using the English language, he made his narratives of the Igbo culture to the wider world, incorporating the Igbo language and proverbs, thereby show-casing the beauty and richness of the African culture. He masterly used the art of story-telling to engage his audience. Achebe in his own words, declared: “In the end, I began to understand there is such a thing as absolute power over narrative. Those who secure this privilege for themselves can arrange stories about others pretty much where, and as, they like.”

His biography page at the University of North Carolina website describes Achebe’s style of writing as “one of the most well regarded styles of current authors, nearly revolutionary in impact... it is actually full of depth and complexity despite appearances. Very realistic and brief, it conveys as close as possible in English the language also spoken by the Ibo. By sprinkling the language with proverbs and other cultural references, Achebe slowly and naturally introduces the reader to Ibo culture. Achebe's honest and stunning style make him the ideal spokesman for African Literature, or as little of it as the West can understand.”

The evidences of his acceptance and global audience are that he has sold 10 million copies of Things Fall Apart. The book has been published in 50 different languages, and has not run out of print.

History has it that Achebe was not the first African to write a novel, Amos Tutuola had written the Palm-wine Drinkard in 1952, while Cyprian Ekwensi had written People of the City in 1954. But Achebe was the first that brought Africa to the world stage with his writing.

Prior to Achebe, literature in the English world was simply referred to as English Literature. However, his invaluable contribution and pioneering role in the development of African writing raised an argument about the correctness of the appellation of all literature in English language as English Literature. This subsequently redefined literature, limiting the scope of English Literature to works by the English people, and recognizing the contribution of other works in English language by people of other nationalities, hence the use of Literature in English today.

His inspiration returned to Africans their words, their sight, and their self-worth.

As the saying goes, “Progress has many friends. But failure is an orphan.” The landmark success recorded by Achebe’s writing, not only gave birth to African Literature, but inspired numerous other African writers to emerge. He was an inspiration and a pace setter.

Prior to the publishing of his first novel, Things Fall Apart, in 1958, Africans depended on the West to tell our story. The impression they gave to the world about us was the way we were perceived. Thus, the image stuck!

It’s noteworthy that his revolution transcended the literary world. It also gave an unwavering footing and backbone to the African to assert their cultural, social and political consciousness. President Nelson Mandela corroborates this when he said that Achebe "brought Africa to the rest of the world, the writer in whose company the prison walls came down".

As our sages say, “nwannunu na agba egwu n’akuku uzo, o nwere ihe na akuru ya egwu” (the bird that’s dancing on the pathway, something must be playing the music for it). For Professor Achebe to stay firm and rooted, he had trained himself to live with numerous sterling qualities, some of which were: integrity, constancy, excellence, responsiveness, forthrightness and outspokenness. These showed up in his dealings. After graduating from the university, he worked as the Director of external broadcast of the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS), worked with the BBC, and played a leading role in the creation of Voice of Nigeria network in 1962. But notwithstanding, he was never blinded by class, fame or fortune. Rather, he always identified with his people. When the Biafran War broke out, his allegiance was not questionable, unlike a handful of elites who took the wrong turn for the sole purpose of massaging their ego. In the same vein, as a man who had acquired Western education, he did not stay complacent in an African society that beckoned for a voice of change. Thus, he never missed an opportunity to be that voice, esteeming our collective good and a common destiny high and above a personal advantage.

When he ventured into politics during Nigeria’s Second Republic, he was frustrated out because of the corrupt practices which typified Nigerian politics. He did not compromise, but chose to put pressure on the government through constructive criticism. He decried the rule by corruption and the failure of leadership. His disposition made those within the corridors of power uncomfortable, and they sought to bring him into the fold by offering him special privileges and accolades which he rejected repeatedly. The Nigerian government under President Olusegun Obasanjo in 2004 recognized him for the third highest national honour (Commander of the Federal Republic - CFR), which he turned down. This was his response to Obasanjo:

“Nigeria’s condition today under your watch is, however, too dangerous for silence. I must register my disappointment and protest by declining to accept the high honour awarded me in the 2004 Honours List.”

And in 2011, the government of President Goodluck Jonathan again recognized him for the same national honour, which he again turned down, saying: “the reasons for rejecting the offer when it was first made have not been addressed let alone solved.”

Instead of giving out national honours at a time the country was in turmoil, and being personally recognized, he persuaded the government to curb corruption, insecurity, and institute good governance which would bring good dividends to the people.

It was said that the American hip-hop superstar, 50 Cent offered Achebe USD 1 million to use his book title ‘Things Fall Apart’ as a title for a movie. But the renowned author declined the offer and kicked against the idea. This shows that Achebe is a man no one could bribe or buy over, irrespective of what is at stake. In an article written by Victor Ehikhamenor, published in the New York Times of March 25. 2013, Achebe was described as Africa’s Voice, Nigeria’s Conscience, a man who taught the younger generation not be hungry to the point of selling their birthrights.

Conclusion:

The lesson we have learnt from Achebe as individuals and as a people is the challenge to see our corporate well-being as much more vital than our individual privileges. Achebe came into the limelight at 28 years of age, remained steadfast to his cause until his death at 82 years of age. His, is a life worthy of emulation. For all those individuals in our midst whose pre-occupation is to tear apart all the fabrics that hold us together, your challenge is to see that great men like Chinua Achebe emerged by sticking with high moral values. And the whole world applauds them, and has written their names in gold.