Igbo People and Irish People: A Trans-Atlantic Partnership By George C E Enyoazu At the 10th Anniversary of Ezinwanne, Drogheda, Co. Louth, Ireland

For the benefit of all, especially our Irish friends, I would like to start by running a little historical introduction of the Igbo people, and then talk on the similarities of the Igbo and Irish peoples, before exploring areas that would be mutually beneficial to both nations.

The Igbo people (Ndi Igbo in Igbo language) are found in their homeland of Igboland, one of Africa’s most densely populated areas.

In his article on Igbo People, VanderSluis, (n.d.) describes the land as ‘rich and fertile crescent created by the lower Niger River’. It goes on to say that the ‘area and its people were one of the driving forces in the early development in the Iron Age which has helped mold the world as we know it. Their culture has brought much to enrich the world’ (VanderSluis in Minnesota State University website). The territory is within the beautiful equatorial rainforest zone. Talking about the richness of the Igbo culture to the world, the Igbo-Ukwu archaeological find, dating back to the 9th Century demonstrates the sophistication of Igbo artistry, innovation, culture, and the openness and engagement of the Igbo in international trade with distant lands, such as Egypt thousands of years ago. Besides, the Igbo-Ukwu find shows that the Igbo people settled in that part of Africa earliest than their neighbours.

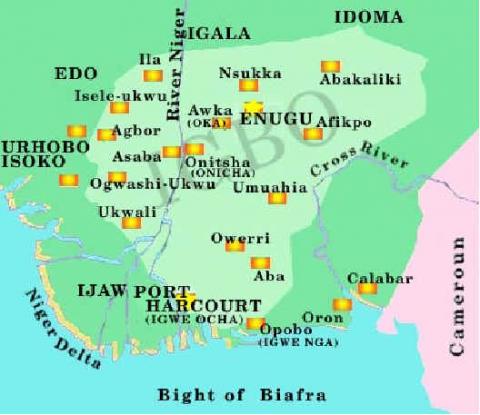

Although officially referred to as southern Nigeria, Slattery, (1999) explains that the Igbo territory is divided into two unequal halves by the River Niger. The two halves are the bigger Eastern region and the smaller Mid-Western region. The Igbo are surrounded by other ethnic groups: Edo, Urhobo, Ijaw, Ogoni, Ogoja, Igala, Tiv, Idoma, Yako, Ekoi and Ibibio. The Igbo nation is one of Africa’s largest ethnic groups with an estimated population of 50 million, and arguably the largest ethnic group in Nigeria. Igboland stretches through Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo, and parts of Delta, Rivers, Akwa Ibom, Benue, Kogi, and Bayelsa States.

Igbo is a recognized minority language in Equatorial Guinea.

Igbo Subgroups include – Anioma, Aro, Edda, Ekpeye, Etche, Ezza, Ika, Ikwerre, Ikwo, Ishielu, Izzi, Mbaise, Mgbo, Ngwa, Nkalu, Nri-Igbo, Ogba, Ohafia, Ohuhu, Omuma, Onitsha, Oratta, Ubani, Ukwani. These have their distinct dialects.

Igbo people, vis-à-vis Irish people are outgoing peoples who share a lot of things in common. Igbo and Irish people have had historical partnerships and interactions. These come under four major categories:

Joint development of the United States of America

Irish Missionary and Humanitarian work in Igboland

Igbo Missionary work in Ireland

Igbo migration to Ireland

Although their people are found across the globe, Irish people have solidly entrenched their presence in America, and Igbo people too are solidly found in America. There are millions of Irish-American people in the US, so also millions of Igbo people. While there are over 40 million Americans who claim Irish heritage, it’s suggested that the majority of African-Americans are of Igbo descent. Research suggests that perhaps 60 percent of black Americans have at least one Igbo ancestor. Igbo people and Irish people contributed to the development of American culture. Some of the phenomenal evidences are the Igbo Landing in Georgia which enriched American history, myth and legend, and the recreation of the Igbo village in Virginia. At the Frontier Culture Museum of Virginia, the Museum’s Old World’s Exhibits include an Igbo West African Farm, an English Farm, an Irish Farm, an Irish Forge, and a German Farm. These farms reconstruct the culture of the major players in Virginia history, and suggest that the Igbo have had a long association with the Irish in building the United States of America.

In 1791, Olaudah Equiano, a former Igbo slave who bought his own freedom and became a strong voice for the abolitionist movement, toured Ireland for 8 and half months, selling 1900 copies of his narrative in Ireland alone. Equiano’s narrative depicted the horrors and cruelty of slavery, and his travels and lectures raised an awareness which turned the public against the Slave Trade.

One common feature between the Irish and Igbo nations is their embrace of Christianity. In fact, the Irish were instrumental in the evangelization of Igboland, courtesy of the Irish missionaries. Our common Christian heritage enhanced our love for education. The Irish (Holy Ghost Fathers) established the Catholic mission schools in all the nooks and crannies of Igboland. The Igbo Catholic Churches and educational institutions were previously run by the Irish, making Igbo school calendar to be exactly the same with the Irish. In those days, the Igbo school system was exactly the same with the Irish. Igboland operated the primary system as opposed to the elementary system. We had the best and qualitative education system. During the era, before a school pupil goes through junior infants, senior infants, first class (standard one), second class (standard two), and third class (standard three), they had already acquired a basic education which opened a world of possibilities for them. And by the time a pupil completes standard six, they were already headed for great things in life. It’s said that the Yoruba nation embraced Western education about sixty years before the Igbo nation did. Commending the meteoritic rise of the Igbo people, Stafford, Michael R., United States Army Major notes:

“The Ibo of the Eastern region were initially quite

different from the hard-working, intelligent people that

developed after the arrival of the British. Isolated in the

dense, wet woodlands of the Niger Delta, the Ibo lacked the

sophistication of the Yoruba or the coastal minority tribes.

In contrast, the originally backward Ibo emerged from the

British colonial period as the most westernized tribe,

espousing Christianity (as did some Yoruba) and proving

adaptable to the imported work ethic due to their initiative

and vigor.”

It’s essential to say that the influence of Christianity, adaptability and industriousness of the Igbo accelerated the rise of the Igbo. Chinua Achebe concurs and describes the Igbo as: “fearing no god or man, was “custom-made to grasp the opportunities, such as they were, of the white man’s dispensations. And the Igbo did so with both hands.” “Although the Yoruba had a huge historical and geographical head start”, Achebe continues, “the Igbo wiped out their handicap in one fantastic burst of energy in the twenty years between 1930 and 1950.”

He recounted the earlier advantage of Yoruba as deriving from their location on the coastline, but as soon as the missionaries crossed the Niger, the Igbo took advantage of the opportunity and overtook the Yoruba.

“The increase was so exponential in such a short time that within three short decades the Igbos had closed the gap and quickly moved ahead as the group with the highest literacy rate, the highest standard of living, and the greatest of citizens with postsecondary education in Nigeria,” concludes Achebe.

It’s noteworthy that the hard work of the missionaries and the Igbo people yielded the desired result by lifting the Igbo to the position where their progress peaked to the envy of others.

At this juncture, in view of Nigeria’s fallen standard in education, I recommend a reversal to the more solid national primary system of education we had before the war. This is vital because good education marks the foundation of any solid economy.

The Irish and the Igbo share the same political philosophy of republicanism. They do their own thing. That’s what Achebe meant when he said that Igbo people fear no god or man. The Irish fiercely fought against occupation of their land, while Igbo did the same and led the fight for Nigeria’s political independence.

The Biafran War marked the darkest era in Igbo history. The war effectively reduced Igboland into ruins, created a scale of starvation and deaths that shocked the whole world. A total of 3.1 million Igbo people...children, women and men died through shelling, blockade and starvation policy by the federal Nigerian government. The Irish Holy Ghost Fathers who worked in Igboland, together with other Christian missionaries rallied round us and created the Jesus Christ Airlines which brought food and other relief materials to save millions of threatened Igbo people. Furthermore, in reaction to the crisis, a combined team of responsive Irish people formed the charity, Africa Concern, which later metamorphosed into Concern International as we know it today. This act of kindness did immensely cushion the effects of the war on the dying Igbo people.

From the afore-said, the cooperation of the Irish and Igbo peoples has been monumental. Every Irishman or woman who walks the streets of Igboland is idolized. Here in Ireland, in 2005, a former Catholic Bishop of Owerri Diocese, Raymond Kennedy (an Irishman) was laid to rest, and his funeral service held in Kimmage, Dublin. Apart from being a former Bishop in Igboland, Raymond’s family had initiated the formation of Concern International. Some of us in Ireland represented the Igbo nation at his funeral service. We met tens of Irish people who had lived in Igboland in various capacities in 1950s and 1960s. They were so excited and expressed their nostalgia about their good old days in Igboland. We were taken aback that they all preferred to speak to us in Igbo language, instead of English, mentioning the places they’d been, lived and worked in Igboland. In fact, they said they would like to return to Igboland. This is the kind of impression Igboland leaves on sojourners in her territory. Igbo people have open arms to accept people. The hospitality of the Igbo people to others hinges on our culture, which forbids the ill-treatment of a foreigner. A popular Igbo adage says: Ojemba enwe iro (A traveller makes no enemies). Because the Igbo travel widely around the world, they also treat others in their land as they would like to be treated in someone else’s land.

After the Biafran war, Ireland was a sanctuary for Dr Michael I. Okpara, the former Premier of Eastern Nigeria. A number of Igbo people had at one time or the other come to study and/or work in Ireland. Emeka Ojukwu, Jr, the son of General Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu studied in Ireland. Recently, globalization, and various pull and push factors have led to the migration of thousands of Igbo people to Ireland, hence, the existence of Igbo Union, Ireland. For more than a decade, these Igbo people have contributed to the growth of Ireland in their various professions – priests, pastors, doctors, IT professionals, academics, lawyers, nurses, business people, carers, etc. Interestingly, the Irish had pioneered the evangelization of Igboland, but today scores of Igbo Christian clergies are here, evangelizing Ireland.

The partnership between the Irish and the Igbo has to be taken to a new level. Igboland is still a virgin land, calling for foreign investment. Igbo people would like to share their beautiful land with well-meaning people, such as the Irish. Our land offers great opportunities in diverse areas, such as education, agriculture (crops, dairy, poultry and livestock), health, hospitality, construction, energy, industry, manufacturing, food processing, cement, petroleum and gas, amongst numerous other sectors.

Igboland is blessed with a host of natural resources for economic and developmental potentials, and mineral-based raw materials for industries, and in commercial quantities. These include:

Crude oil (petroleum), Natural gas, Salt, Lead (a chemical element used in building construction, and many other sectors), Zinc (a metallic chemical element), Kaolin, White kaolinite clay (used for ceramic and porcelain industry), Fine sand, Limestone – used in architecture, and Natural gas, Coal – a raw material for power generation station which powered the whole of eastern Nigeria up to the civil war. Other minerals include Laterite clay ‘a source for aluminium ore’, Ball clay (Lignite) used to impart plasticity and aid rheological stability during the construction of ceramics, Iron-ore rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be extracted for economic purposes, Glass sand used for manufacturing glass, Gypsum - used for the manufacture of fertilizer, Silica sand - ideal for agricultural produce, such as crop cultivation, Ceramic clay, Refractory clay – used for making pottery, and Granite (Igneous rock) consisting of quartz and other materials. Granite is used for antiquity, sculpture and memorials, buildings, engineering works, etc. Many other resources include Clay; Iron stone, Sand stone, Pyrite, Tar Sands/Oil Shales, Copper, Phosphate, and Industrial Sands. Cash crops also abound, including: rice, yams, potatoes, maize, beans, cassava, cashew, palm-produce, groundnuts, melon, banana, plantain, and assorted kinds of fruits and vegetables.

Irish private and public firms can invest in any of the sectors in Igboland, including private universities, schools and colleges, and healthcare system. Just like the Americans site American universities in different parts of the world, it would be a welcome development to have an Irish university sited in Igboland, as Igbo people would easily fill the consummate demand. All Igbo people in Ireland should live above board and engage in our traditional enterprising spirit, and partner with Irish entrepreneurs to invest in Igboland. State governments in Igboland are ready to welcome investors into any sector of our economy with incentives. We would be pleased to bring clarity to any grey areas potential investors may have pertaining to this lecture. Above all, there’s a need for cultural exchanges between Igboland and Ireland, which I suggest the Igbo Union should take up, and facilitate. When these are done, a lasting and vibrant trans-Atlantic partnership will be solidified on all fronts between the Igbo and the Irish.

Thank you so much for your time. God bless you all!

George C E Enyoazu

President-General, Igbo Council of Europe (ICE)

www.igbocouncilofeurope.org